Inflation is the moth that eats away at your savings. It is the hidden tax on the asset side of the world’s balance sheet. For the British, inflation revives memories of the 1970s, when the UK begged the IMF for a bailout, there was only enough electricity for a three-day working week and bin-bags piled up in the streets. How can inflation possibly be described as a good thing?

The simple answer is that one person’s loss is another’s gain. While asset owners’ wealth is nibbled away by inflation, debtors can raise a patient smile. For the inflationary moth will be munching through both the value of wealth and the value of debt.

Inflation is great for debtors, but can equity investors also benefit from price rises? They can – at least in the short-term.

Demographics may be steering long-term inflation

First, though, it is worth considering that we may be heading for an inflationary future for reasons quite apart from the vast stimulus packages and piles of debt that have been racked up in a bid to counteract the economic effects of COVID-19.

Recently published, The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival[1] makes the case that inflation is tethered to the size of the global labour force. If labour is abundant, then inflation will be quiescent. If, however, the working-age population starts to fall, then inflation will start to flex its muscles.

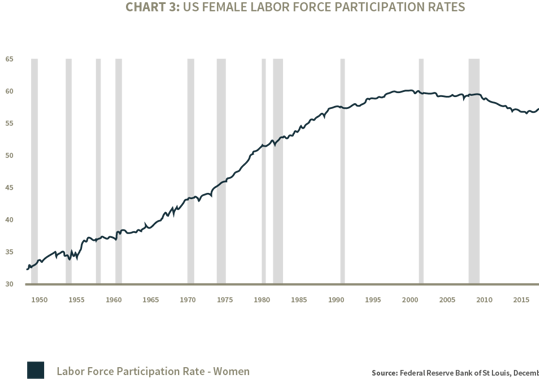

We are, the authors argue, at a demographic tipping point in world history. The rise of China, the fall of the Berlin Wall, increased female participation in the labour force and the baby boom generation all provided the world with a flood of new labour sources. These trends are reversing and the steady pattern of weak inflation we have lived through since the 1970s is likely to disappear over the next few decades.

It does not feel as if “the rise of China” requires the past tense, but if we limit ourselves to demographic shifts in this vast country there are ominous changes afoot. Between 1990 and 2017 the working-age population of China rose by over 240m versus a 60m rise in Europe and the US combined.

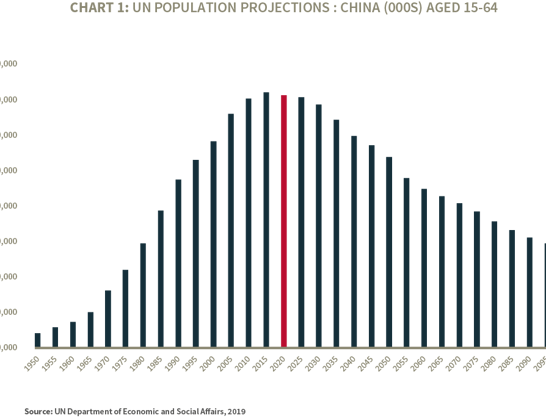

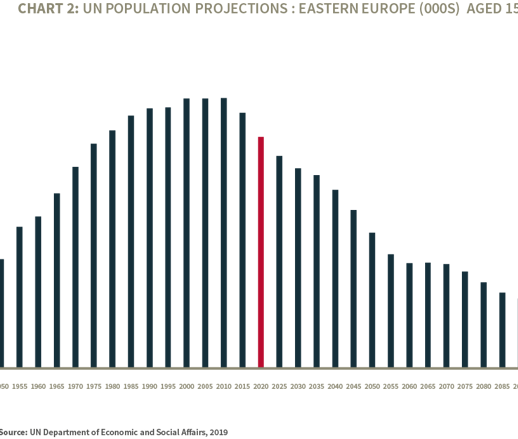

The UN’s Population Projections (Chart 1) see China’s working-age population of people aged 15-64 falling from its current level of just over 1bn to under 800m by the year 2050. Turning to Eastern Europe, the boost to the global labour force that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall will continue to dissipate, with the region’s working-age population in Eastern Europe expected to decline by 20% over the next 30 years.

Meanwhile, the rise in female workplace participation rates in developed markets peaked in the years preceding the 2007-8 Global Financial Crisis, as we can see from these stats from the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (Chart 3).

Finally, the great post-war baby boom generation has now downed tools and keyboards and joined the world’s ever-growing number of retirees.

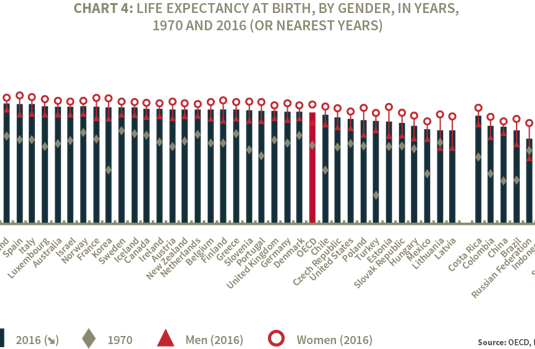

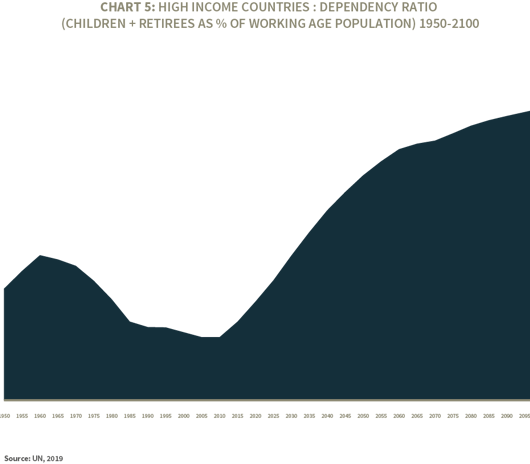

As baby boomers joined the labour force at a time of falling fertility, the dependency ratio declined sharply. During the past decade this trend has started to reverse, because baby boomers and future generations can look forward to an increasingly long retirement. Better pills, scans and higher spending on healthcare have prolonged life in developed countries by around 10-12 years over the past five decades. As a result, the UN projects a rapid rise in the dependency ratios of high-income countries in the years to come.

This matters for inflation because children and retirees consume but do not produce. If there is more demand for goods and services and fewer people supplying them, then common sense suggests that prices for goods and services will rise.

Covid shock

These four long-term trends, the authors argue, are the kindling that will slowly warm the inflationary pot over the coming years and decades.

What of the short term? Sadly, there is nothing slow about the spread of COVID-19 or its impact on the global economy, which has spurred central banks to vastly increase quantitative easing in a bid to keep interest rates low, support economies and financial markets, and stimulate recovery.

Debt now has almost no cost and savers are confronted with negative real interest rates. This combination has propelled equity valuations sharply higher as investors pursue real returns and, in the process, are able to leverage their investments at negligible cost. It also presents governments and central banks with a dilemma.

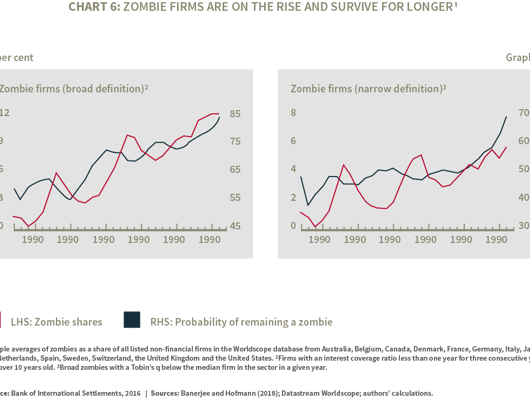

The US market’s inflationary expectations are the highest in eight years, at a time when high levels of corporate debt coupled with poor profits have turned many companies into “zombies” – companies that are unable to cover interest payments from profits.

The number of zombie companies has increased steadily across the developed world. One recent study finds that the corporate undead now account for 30% of the Russell 3000, exceeding levels seen during the dotcom boom (29%) and the aftermath of the 2007-8 Global Financial Crisis (25%).[2]

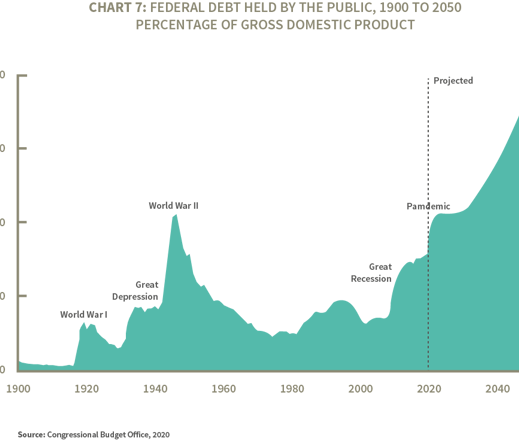

When you combine the weak state of many a corporate with government debt (US debt is now higher than during WWII), governments have a strong incentive to keep interest rates low in a bid to prevent corporate collapses and let inflation erode the value of debt.

Inflation – your short-term friend

As consumers start to spend the cash hoards they have built up over a long lockdown winter, inflation may tick upwards. Central banks will not be in a hurry to raise interest rates to douse price rises, which means negative real interest rates are likely to increase. That is not a happy place to be if you are a bond holder with a fixed coupon.

By contrast, stocks in companies that can pass costs on to their customers are likely to be in high demand as one of the few places where investors can make a positive real return on their investments.

Investors re-allocating some of their portfolios from bonds to equities, a post-lockdown vaccinated world going on a spending spree and wages taking a bit of time to adjust to inflation. All this will look good on many a corporate balance sheet. If you are an equity holder, inflation can be your friend in the short term.

In the longer term, however, markets tend to re-price companies’ returns and prospects to reflect more realistic expectations. Returns on equity can increase in only five ways. You can sell more stuff, you can take on more debt, pay less interest on your debt, pay less tax or lower your costs.

If inflation becomes endemic, only one of these five will be heading in the right direction. Yes, rising prices will lift sales, but they will also lift wages and other costs and make debt more expensive. Whatever the efforts of central banks, debt will never be as cheap as it is now, so the interest bill will grow. Finally, given the vast amount of government debt used to support the wider economy, tax rises seem inevitable.

A dose of inflation can be something for equity investors to look forward to. If inflation expectations start to build over the coming months, we can expect to see strong demand for stocks that are perceived to be inflation friendly. But like any good party, you need to pick your moment to leave. Hangovers are no fun.

Important Information

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount invested. Income from investments may fluctuate. Currency fluctuations can also affect performance.

The information contained in this document is provided for use by investment professionals and is not for onward distribution to, or to be relied upon by, retail investors. No guarantee, warranty or representation (express or implied) is given as to the document’s accuracy or completeness. The views expressed in this document are those of the fund manager at the time of publication and should not be taken as advice, a forecast or a recommendation to buy or sell securities. These views are subject to change at any time without notice.

This document is issued for information only by Canada Life Investments. This document does not constitute a direct offer to anyone, or a solicitation by anyone, to subscribe for shares or buy units in fund(s). Subscription for shares and buying units in the fund(s) must only be made on the basis of the latest Prospectus and the Key Investor Information Document (KIID) available at https://www.canadalifeassetmanagement.co.uk/

Canada Life Asset Management is the brand for investment management activities undertaken by Canada Life Asset Management Limited, Canada Life Limited and Canada Life European Real Estate Limited. Canada Life Asset Management Limited (no. 03846821), Canada Life Limited (no.00973271) and Canada Life European Real Estate Limited (no. 03846823) are all registered in England and the registered office for all three entities is Canada Life Place, Potters Bar, Hertfordshire EN6 5BA. Canada Life Asset Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Canada Life Limited is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.

CLI01834 Expiry on 01/03/2022

[1] The Great Democratic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality and an Inflation Revival, by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan. Published by Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[2] William Barritt, CFA, Segall Bryant & Hamill. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/beware-of-zombie-companies-running-rampant-in-the-stock-market-2020-11-24